This is a short version of the Swedish original report. The full version of the project report is available in Swedish Metod för värdeskapande öppna data.

Table of content

Introduction

In order for public sector and governmental agencies to manage the increased pace of technological change and demands from society to deliver valuable digital services they need to collaborate and form partnerships with new and wider range and actors. To stimulate the development of digital services on a competitive digital market, public sector needs to provide and develop valuable digital resources, capabilities and structures to keep pace with the digital development. Open source, data and standards are examples of important mechanism and digital resource that can be used to network and collaborate with public, private and non-profit organisations.

The purpose of the project method for collaboration and value creating open data is to highlight mechanisms that generates added value between public organisations collaborating with companies and third-party developers operating on the open market. A lesson from previous studies was that third-party developers needed some form of relationship to gain insight into future strategic changes that affected their own ability to provide competitive services. For this reason this study interviewed organisations that have a formalised partnership with Swedish Transport Administration and how they perceive value-creation within alliances. The intention is to broaden the understanding about value-creation mechanism from strategic collaborations perspective and how they impact third-party developer. First the study established a theoretical lens to get an perspective on value-creation and how it manifested within strategic alliances and collaborations.

Theoretic lens

To understand digital value-creation between collaborating organisations which sharing and using each other’s digital resource, a theoretical framework is established. This lens provides a perspective of value-creating mechanisms in strategic alliances and collaborations between organisations.

Digital value-creation

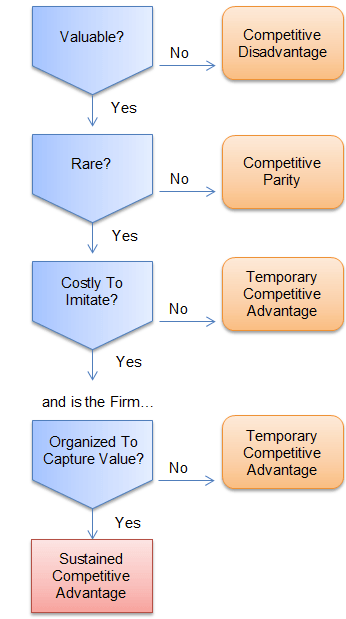

Resource-based view is a way to view value-creation by understanding how firms use resources, abilities, culture and structures on an open market to create competitive advantages1. The perspective is based on how firms combine their tangible and intangible resources such as infrastructure, buildings, company structure, know-how, knowledge, hallmark etcetera to generate competitive advantages.

In order for the resources to cause advantages they need to be difficult to imitate so other firms cannot easily acquire similar resources, for example by buying equivalent software on the market. In addition to resources, the firm needs capabilities to make the most of the resources that they have access to. For example, it can be access to skilled personnel who can utilise decision support programs and analytic tools to gain tactical and strategic advantages. To obtain sustained competitive advantages a firm’s need to possess resources that are difficult to imitate in combination with the capability to utilise the maximum potential from them. However, if the firm does not have valuable resources or the capability to utilise the resource efficiently, it can lead to competitive disadvantages.

IT business value

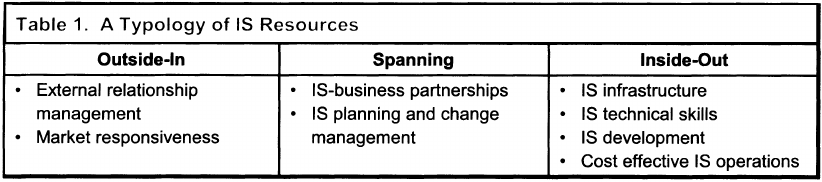

IT business value is theory based on resource-based view. IT business value theory expands the concept of resources to include resources that extend beyond the firm since IT systems facilitate coordination of processes over organisational boundaries2. The theory is also more focused on intangible resources linked to information systems, where IT-related capabilities and resources are central to firms ability to acquire competitive advantages. Capabilities of employees are also considered a resource. Wade & Hulland identified three types of IT skills3.

According to the classification, there are IT capabilities and resources that are developed from an internal focus – inside-out. The motive for developing these capabilities and resources is based on internal requirements to obtain efficacy and adapt to the market. For example, it may be a decision to purchase a new business system to streamline internal administration. An ERP system is a resource that can be procured, but in order to gain competitive advantages the firm needs to possess or hire the skill to integrate and adapt the system to its own operations. According to the resource-based view, a new ERP does not lead to any competitive advantages, since the resource is not rare and it is not particularly costly or difficult to imitate. Knowledge of adapting it to different businesses is not a unique capability either, since the knowledge is probably available on the open market.

External IT capabilities – outside-in – are the knowledge and skills needed to adapt to the market, customers and partners needs. Outside-in IT capabilities are based on previous experiences of collaborating and managing the relationship with external firms and customers, such as integrating processes and IT systems with subcontractors. Another outside-in IT capability is to adapt IT strategies to market changes. To adapt and develop IT strategies rely on the capability to analyse market changes and quickly change internal strategies when needed.

To bridge these two capabilities, Wade & Hulland explains that companies need cross-organisational capabilities – spanning capabilities, to link external requirements with internal. Spanning capabilities prove to be important for creating synergies in strategic collaborations. These capabilities depend on how well different functions and departments are integrated with each other internally. It determines how quickly the company can adapt to the market and external needs. Companies that have fragmented processes and information systems find it more difficult to achieve synergies through collaboration with external partners. Another important spanning capabilities is to be able to lead change projects which originates from external pressure by predicting and planning change projects based on how the market develops, new technology, standards and directives. When internal and external IT-related capabilities align with each other firms can refine and develop value-creating, difficult-to-imitate resources and capabilities that give rise to temporary or sustainable competitive advantages.

Data gathering and methodology

The primary data source for the study consists of twelve interviews with railway operators and freight companies who collaborates with the Swedish Transport Administration. The interviews were conducted through personal meetings between March and September 2017. The respondents in the study have a strategic roles and responsibilities for IT infrastructure, IT system and traffic planning. The interviews were semi-structured and focused on the respondents perspectives on digital value-creation within the partnership with the Swedish Transport Administration.

The study uses thematic network analysis to identify recurring themes in the interview material 4. To attain validity for identified themes, the study follows heuristic guidelines for ensuring thematic saturation 5. In order to explain concepts within informatics, strategic management and economic theories, a combination of deductive and inductive method is used to allow a certain level of openness and at the same time build on constructs from previous research 6.

Result

Global themes

This section presents global themes and general value-creating mechanisms identified in the survey. The global themes consist of organisational and basic themes which are omitted in the English version of the report. Please refer to original Swedish version of the report to take part of quotes and images of thematic diagrams presented below.

Interoperability

The theme reflects the need for an IT infrastructure that enables sharing, combining and reusing digital resources in a standardised approach. Interoperability includes a flexible IT infrastructure that makes it possible to seamlessly exchange and combine digital resources between partners without the need of integrating IT systems. In the survey, the respondents describe a lack of interoperability in the form of fragmented IT infrastructure and IT systems used within the partnership. This affects information exchange in every aspect, from handling traffic deviations to strategic planning and resource allocation of railway infrastructure.

The lion’s share of the respondents describe that the IT systems used in the partnership cannot exchange and reuse basic data and information with each other without integration. This means that the partners have to manually copy, call or send email to obtain information needed to handle time-critical situations such as traffic deviations.

One of the reasons behind the lack of interoperability is described as being too much focus on the procurement of IT solutions and functionality which contributes to the fragmentation. This is a recurring theme that affects different parts of the collaboration, where partners feel that internal departments at the Swedish Transport Administration implementing projects and conducting various change management initiatives without looking at the whole and the need for a more flexible and interoperable IT infrastructure. In order to counteract the increased fragmentation and creation of information silos that usually occur when new IT solutions are introduced.

The respondents stress the importance to make more basic data available than today in combination with adhere to good design principles to create interoperability. To achieve the potential of digitalisation, more digital resources need to be published which can be re-used to create valuable services. For example, access to historical and current train delays and maintenance status, bottlenecks, speed, temporary speed limits etcetera. To better predict traffic flow and be able to use data in digital services which gives travellers a better opportunities to choose the best mode of transport at any given moment.

In order to make processes, concepts and information structures that are difficult to understand more accessible, standardisation and access to models and metadata are needed. The respondents describe that they spend valuable time interpreting concepts and deducting meaning of fragments of information in order to put them into context and to be able to use them, since there are no models, taxonomy or ontology available.

Open source and standards contribute to the creation of interoperability and flexible IT infrastructure. This is due to the fact that open source software components are designed to be used for various purposes and are based on open standards. Furthermore, it enables greater involvement of actors within and outside the transport industry sector since well-known standards and software components are being reused. For example, partners who have built much of there IT infrastructure on open source and standards have led to easier and faster integration with subcontractors and made it easier for them to publish open data for third-party developers.

Congruent structures

The theme congruent structures relate to how well a business is organised to collaborate and create added value in an alliance with others. How a business is organised and structured is described in strategy documents, organisation chart, directives, culture, process maps et cetera. In order to facilitate value-creation, collaborative businesses need to have resembling structures to quickly and efficiently implement decisions, change management, capabilities and structures to absorb and transfer knowledge to stay competitive.

An important structure identified in the study is the need for systematic and transparent information management for decision making within the partnership. When information management structures and processes are not aligned it will create obstacles and complicates collaboration between partners. The respondents describe insufficient structures for exchanging information and situational awareness when traffic deviations occurs. The problem described is that general communications channels such as email, chat and telephone are used extensively, which results in information becoming unstructured and difficult to reuse for different purposes.

The lack of systematic handling contributes to information overload, which makes coordination of traffic deviation more difficult since all the information is spread to all actors regardless of whether it is relevant to their situation or not. In order to solve the problem, better structures are requested for working with scenario based information sharing. The systematisation of information management also includes the utilisation of feedback from partners concerning operational and strategic issues. This is seen as important for working with continuous quality improvement and prioritising issues that are important for partners.

Another structure that has been identified is the different meeting forums that are used within the partnership for resolving and coordinating issues. The various meeting forums handles both practical and strategic issues. For some of the meeting forums there is lack of interest partly because issues that are addressed are too general and the participants feel that their issues are not given a high enough priority. In order to come to terms with the lack of interest, the respondents advocates for clearer objectives and delimitation of issues that the forum addresses. In addition, they urge those responsible for the forums to ensure that people who participate have the right prerequisites knowledge and background to ensure productivity when congregate.

The need to adapt the business or the part of the business that collaborates with certain types of actors is reflected in the fact that some partners created specific structures to cooperate with service developers and third-party operators at arm’s length distances. To facilitate communication with this group of actors, these respondents have created a specific structure for managing collaboration and interaction. The most common structures amongst the respondents are digital portals to provide documentation, FAQ:s, API gateways, meeting calendars, user-forums, et cetera. For example, some of the respondents provide structures to encourage third-party services by providing portals and arranging recurrent developer meetings for software developers. Partners who created these structures also have an explicit strategy to cooperate with third-party developers and provide data and information to foster development of services for the transport industry.

Synergy-creating capabilities

This theme highlights the need for good insight into partners activities in order to identify common goals and utilise each other’s resources in a way that gives rise to synergistic effects. Those who lead and coordinate collaboration within the partnership needs to possess the ability to anticipate future requirements and objectives amongst partners. This requires continuous updating of partners needs and goals, and are described by the respondents as having one’s finger on the pulse.

The understanding of partners needs are said to vary between different departments at the Swedish Transport Administration which coordinates the collaboration. Respondents for example refers to a major change project for process and IT system concerning capacity planning of railroad. That according to the original project requirement specification, would lead to that important processes and IT integrations would ceasing to work. Thanks to partners demands for participation in the project, an in-depth understanding of each other’s needs and goals were achieved, which led to improved value-creation by allowing internal and cross-organisational processes to be scrutinised and harmonized between parties.

One important principle to create synergies are the ability to align different actors perspective of challenges to achieve goals and to minimise ambiguities about the overall objective. This is important both internally and between collaborating partners. Lack of this ability can create uncertainty about the objective and who has the mandate to make a decision. For example, one respondent describes that they had to support the project managers view of the when there was divergence about the overall project objectives with the management of the Swedish Transport Administration.

Synergies also arise when an organisation possesses the ability to combine new technology with organisational objectives. This is done by utilising the properties the technology offers to achieve business goals. Synergies can also be created within a partnership if they can benefit from the technology and integrate it into business. This requires that both parties have knowledge of the technology and the ability to implement it in their own operation. The respondents see it as paramount to harness new features that technology provides and utilise new thought patterns to keep pace with the digital transformation. The capability to identify and exploit properties that new technologies provide is also an important prerequisite and good starting-point to creating interoperability.

In order to obtain knowledge of new technologies, respondents express the need for the ability to collaborate with service developers and third-party developers outside existing partnership. This can give rise to value-creation because third-party developers provide valuable services and customer focus to the industry. Collaboration with these actors requires other capabilities since these actors operates under different conditions where much of the interaction takes place at arm’s length distance between customers and service providers compared with the alliance amongst railway operator and freight companies.

Respondents who have developed the capability to interact with third-party developers see it as strategically important to have control over the interactions through development of portals and API gateway themselves in order to quickly adapt to external requirements. The capability to interact with third-party developers has links to the previous global theme of providing congruent structures to collaborate with different types of actors. In the case of third-party developers these structures can consist of user community and hackathons to facilitate knowledge transfer, exchange of ideas, and opportunities to test temporary collaborations.

Discussion

There are few studies that have explored value-creating mechanisms which leads to competitive advantages between collaborating private firms and public sector from an IT perspective. The intention of the study is to increase the understanding of central mechanisms to creating value-creation within strategic collaborations between the public and private sectors from an IT perspective. Furthermore the study hope to increase the awareness of factors that are important to accomplish digitisation of industries where collaborations between public organisations and companies are common. Railway operators that partnered with the Swedish Transport Administration are dependent on the authority’s resources, structures and abilities to offer competitive services on an open transport market. The collaboration mimics a market situation where actors are part of a value-chain with other actors and where surrounding market conditions affect collaborating partners abilities achieve competitive advantages78.

The value-chain is used as viewpoint on how resources are used and refined between collaborating firm with an overall goal of providing competitive services. The respondents in the study uses available resources within the partnership in combination with their own for creating transport services. Similarly, third-party developers are dependent on other actors in the value-chain to create services using resources made available on digital platforms. In both cases, it is a conscious and strategic decision to use the available resources and thereby creating dependencies between actors in the form of a value-chain.

The study finds support in literature that the tree identified value-creating mechanisms within the partnership of respondents also have implications on third-party developers which operates more on an arm’s length distance. Although there are limitations on generalisability for how much the mechanisms affect different types of strategic collaborations. Within the collected data for the study it is not possible to determine how a specific value creating mechanism affects alliance partners versus arm’s length distance relationship. To better understand how different value-creating mechanisms affect different types of partnership, further studies are needed to investigate the interaction between different value mechanisms and forms of collaboration.

Conclusion

The study presents three overall value-creating mechanisms that are important in collaboration between public and private organisations who operates on an open market. This is important for public sector and governmental agencies that collaborate with the private sector to shed light on mechanisms that affect private firms ability to provide competitive services.

The mechanisms identified in the study are assumed to be generalisable for other types of strategic collaborations where actors are part of a value-chain and are dependent on each other’s resources, abilities and structures to create competitive services. According to the arguments in the discussion, the mechanisms also influence the value-creation in collaboration with third-party developers at arm’s length distance. The main argument for this is based on the fact that third-party developers also are classified as a form of strategic partnership and need to relate to the other actors resources, abilities and structures which are part of the value-chain.

However, there are limitations to the importance of the mechanisms for different types of strategic forms of cooperation and their relevance to actors that are not dependent on a value-chain to create competitive services and products. There is a need for further studies to identify the mechanisms impact for organisations that control the whole value-chain themself. Or organisation that does not posses their own and redistribute other organisations digital resources–data. Such as open data portals, communities and similar actors.

Last Updated on 2021-03-18

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. Retrieved from http://jom.sagepub.com/content/17/1/99.short

- Melville, N., Kraemer, K., & Gurbaxani, V. (2004). Review: Information technology and organizational performance: An integrative model of IT business value. MIS Quarterly, 28(2), 283–322. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2017226

- Wade, M., & Hulland, J. (2004). Review: the resource-based view and information systems research: review, extension, and suggestions for future research. MIS Quarterly, 28(1), 107–142. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2017218

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Walsham, G. (1995). Interpretive case studies in IS research: nature and method. European Journal of Information Systems, 4(2), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.1995.9

- Porter, M. E., & Millar, V. E. (1985). How information gives you competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.481

- Melville, N., Kraemer, K., & Gurbaxani, V. (2004). Review: Information technology and organizational performance: An integrative model of IT business value. MIS Quarterly, 28(2), 283–322. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2017226